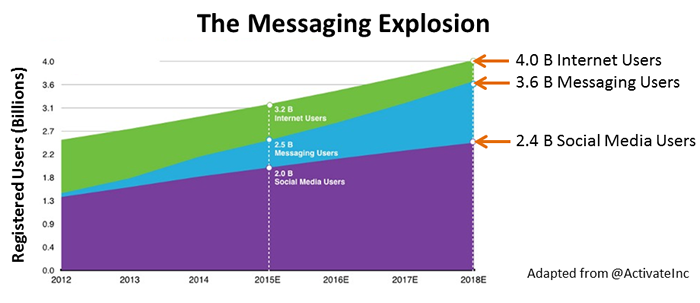

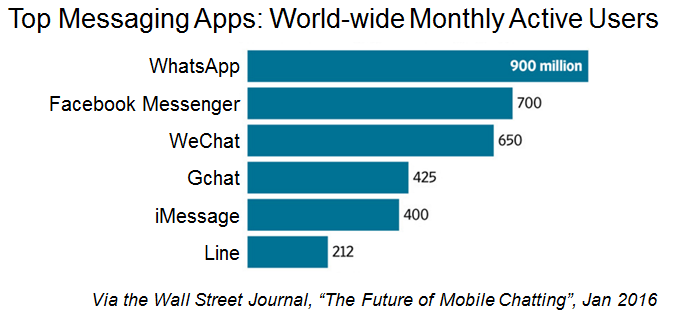

Messaging is growing at a breathtaking pace. The top 4 messaging apps have almost 3 billion users. In particular, China-based WeChat has been the center of attention both for rapid growth and for pushing the “messaging-as-interface” model further than anyone else.

For WeChat’s 600 million users, it is not just a way to chat with friends, it’s also their primary gateway for interacting with, and buying from, companies. WeChat has leveraged popularity in person-to-person (P2P) interactions for expansion into business-to-consumer (B2C) interactions. So much so, that it’s more important for a new company in China to have a WeChat account than a stand-alone website.

Naturally, many people are asking, “Who will be the WeChat of the West?” You can find variations on that headline in articles from Re/Code, Wall Street Journal, TechCrunch and GigaOm. But is that even the right question?

What’s the Right Question?

When people ask, “Who will be the WeChat of the West?” they are really saying, “Which of the existing messaging platforms can extend from P2P to B2C?”

Every major messaging platform has signalled its intention to head in this direction:

- Facebook announced Messenger for Businesses in April.

- WhatsApp announced a new plan 2 weeks ago.

- Kik has stated plainly their desire to be the “WeChat of the West”. (I believe it was their CEO Ted Livingston that coined the phrase.) The large investment they got from WeChat itself will certainly help.

- Snapchat, another WeChat investee, has a similar plan.

Internet giants Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft are also looking hard at this, driven by a mix of envy/fear. Envy because WeChat’s lock on both P2P and B2C communication is unprecedented and lucrative. Fear because they worry this alternate model – messaging as an interface for everything – can erode their role as gatekeepers.

A post by a16z’s Connie Chan explains the interest in WeChat’s model: “First …it points to where Facebook and other messaging apps could head. Second, [it] indicates where the future of mobile commerce may lie. Third, it shows what it’s like to be both a platform and a mobile portal.”

But everyone is forgetting that it takes two to tango. If you want to operate a B2C messaging platform, it must also be appealing to the “B” part of that, i.e. the myriad service and retail companies that consumers want to communicate with. How does this appear from their perspective? If you’re a company busy trying to spread a limited budget across an increasing number of channels (call center, email, chat, social media, etc.) does this new thing help you or hurt you?

The next few sections will dig into that question, but here’s the short version:

- Chat is great for customer service and companies universally want more of it.

- Chat adoption, particularly on mobile, has been hindered by two big problems.

- Messaging can solve these two problems, but it comes at the cost of ceding control to the messaging platform.

The Appeal of Chat

Chat is the fastest growing channel for customer service. Its effectiveness is well-established, with cost-per-contact substantially lower than phone calls, and customer satisfaction generally high. Its shortcoming is uptake, particularly on mobile, where the client interface falls short. So messaging could be the solution to that problem. See last week’s post Is Messaging the Messiah for Customer Service?

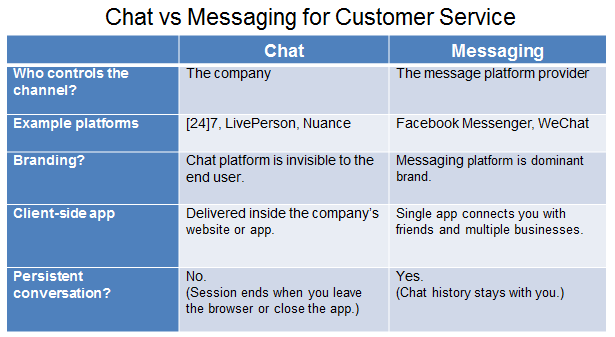

A quirk diversion on terminology… Although “chat” and “messaging” are interchangeable in casual usage, they refer to very different things in the context of customer service.

A company adds “chat” to its website or mobile app by buying, from a 3rd party, a service that will live solely on that company’s site or app. Whereas, “messaging” is something that requires the company to partner with a platform that gives consumers a single interface (on the web or phone) for contacting both friends and businesses. The company does not pay for the platform and does not have control over it. (Those definitions aren’t official, but seem to be the consensus of the analysts and industry folks I spoke to.)

The chart below fleshes out the comparison.

Messaging Solves Mobile Chat’s UX Problem

Given how popular chat was when confined to the web world, it was expected that usage would skyrocket on mobile. But adoption has been held back by the lack of a good user experience (UX) for mobile chat.

If your company wants to extend your web-based chat to your mobile users, you can use the same back-end, but for the front-end – the customer-facing piece – your options aren’t great.

- You could release a mobile app with an embedded chat component (aka “in-app messaging”), but consumers have limited appetite to download apps. (Unless there is a lot of appeal beyond just the customer service function and there is a long-term relationship with the company.)

- You can repurpose the web-based chat interface through a mobile browser, but that’s awkward for the user and won’t always work.

- You could chat over SMS, which is available almost universally, but not free for all users, and excludes tablets.

All of these options are in use successfully today, but at a scale that is far below the potential of mobile chat.

On the other hand, if your company partners with Facebook Messenger the odds are good your customer already has the client on their mobile device (It has 800m daily users, after all). And if they don’t have it, there’s a better chance they will download it, since it offers utility beyond just talking to your company.

Messaging solves the mobile UX problem by capitalizing on the pre-existing broad distribution of client software.

Messaging Solves Mobile Chat’s Discovery Problem

In addition to the mobile UX problem, there’s also this: Given all the possible ways that a company might make chat available, how is someone supposed to know which avenue is the right one?

Imagine you’re a mobile consumer interested in chatting with Company X, and you don’t know a priori which options for chat are available. What will you do? Some options…

- Web-based chat: You could go to their website, look for a chat option, and see if it is mobile-compatible.

- App-based chat: Assuming you don’t have the app yet…. Go to the appstore, search, download, hope they have chat.

- Twitter: You could look up their handle, send a tweet and see if they respond.

- SMS: You could get their number (sometimes this is tricky), send an SMS and wait for a response. (And hope that response is useful.)

How much tolerance do you have for trial-and-error? How many dead-ends will you endure before you simply pick up the phone?

Now, people will say “Company X is very responsive on Twitter” or “Company Y has a great mobile app with chat”, but that’s not the point. The point is, how does the consumer know that? This is a problem of DISCOVERY.

Even if a customer prefers the experience of a text-based chat to talking on the phone, the phone call is a “sure thing”. Whereas the risk-adjusted effort of searching for and initiating chat outweighs the improvement in experience.

Any sufficiently popular messaging platform can solve the mobile UX problem. But only WeChat has solved the discovery problem. It did that by reaching a critical mass such that consumers in China can assume the company they want is available through that channel. By the same token, companies feel they need to be on WeChat to be competitive, and thus the positive feedback loop is complete. This is similar to Google’s dominance in search.

WeChat is the first time both mobile UX and discovery have been solved for B2C chat.

But, Who Controls the Channel?

If messaging can deliver the cost-efficiency and customer satisfaction of chat while making it popular on mobile, every consumer-facing company should be eager to sign on. But there’s a catch.

A major differences between chat and messaging is who controls the channel (see chart above). Let’s say Company X uses a chat vendor (e.g. LivePerson, [24]7, Boldchat , OLark) to add chat functionality to its website or mobile app. There is a vendor-client relationship there. Company X is paying and the vendor needs to keep its client happy. The same is not true if Company X partners with a messaging platform (e.g. Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Kik, SnapChat). What are the ramifications of this?

First, there is the issue of data ownership. The platform owner will clearly be able to “see” the communication between consumers and companies. What, if anything, is it allowed to do with that information? Is this a situation similar to Gmail using your email content to target ads? Can Facebook target ads based on what you say in a chat with, say, Avis? How about just the fact that you chatted with Avis? Certainly Hertz would be willing to pay extra to serve ads to those folks.

Second, there is the issue of neutrality. What if you commit to using a messaging platform for your customer interaction and then the owner of that platform invests in a business that competes with yours?

This is not a theoretical concern. For example, WeChat is blocking Uber in order to help a rival ride-sharing company; one which is an investee of WeChat’s parent, TenCent. Take a look at the list of investments and acquisitions by TenCent (sometimes in secret) and consider their ability to play “kingmaker”. (Great analysis on that point by Jeff Richards and Jixun Foo here.) This is a side of the WeChat success story that is rarely talked about.

A Tough Choice

Companies face a tough choice. They are very eager to move conversations off the phone (where cost is highest) and on to chat. The fastest way to get there may be by partnering with a messaging platform, but doing so means giving away some control over a critical part of their operation. Is that a smart move or a deal with the devil? Is it akin to the power that Apple got by becoming the gateway for music purchasing? Or is the difference between an “owned” and “shared” chat system just incremental?

So when you hear someone talking about a platform becoming the “WeChat of the West” keep in mind that there are two big chasms to cross: Getting large scale consumer adoption AND convincing enough companies that it is in their interest.

Discover the Contact Center Trends That Matter in 2024

Dig into industry trends and discover the changes that matter to your business in the year ahead.